Reassurance is a Strategic Capacity

Part of the reality of this moment is the epistemic blindness against good things that are intangible or hard to measure.

That is why we have made analytical arguments in defense of otherwise self-evident virtues such as joy, imagination, and empathy.

Today’s letter is about the requirement for reassurance.

- Meet John Hench

- The Performance Economy's missing piece

- Reassurance is a strategic capability

- The meaning of perfection

- PRACTITIONER INSIGHTS

- SOURCES

Meet John Hench

You may not know his name, but you know his work. John Hench was one of the original Imagineers at Disney who created, among other things, the idea of the theme park.

Frank Gehry said this about Hench:

“There are certain people, and John is one of them, who bring a really special quality, one that’s almost indefinable, one that can take “good” and make it “great.” John’s ability to do this, I think, is rooted in his curiosity and his love of people…. Even when the specialists have given up, John will come in and suggest a simple and elegant solution – one that has never even occurred to anyone else.”

Hench was a designer and draftsman, a gifted generalist who bravely tackled and licked problems of all sizes. The logic behind his approach is an enduring legacy.

Hench believed in the primacy of reassurance.

The survival thesis

Hench's approach to design starts not with aesthetics but with biology. He believed humans are constantly, subconsciously scanning environments for threats. "Audiences respond to our animated movies because they are about survival," he told a small group at a luncheon, the details of which were captured for posterity.

"Survival is the basis for all games." His design philosophy flows from this: if the default human state in an unfamiliar environment is low-grade vigilance, then the designer's first job is to resolve that vigilance; to communicate there is nothing to fear before asking anyone to engage, learn, buy, or play. "What we are selling is not escapism but reassurance."

Contradiction as threat

Hench identified visual contradiction as the primary trigger for environmental anxiety. He used a specific example: a Gothic tower on a Los Angeles street with a gasoline sign in front of it. The emotional image of the tower is destroyed; the sign doesn't benefit either. "When there are contradictions, when there is chaos, we feel threatened." Disneyland's power comes from eliminating these contradictions. Every element reinforces every other element. There are no competing messages.

Order produces freedom, not control

The common critique of Disney’s approach to theming is that it's controlling; scripted, managed, sanitized. But Hench's observation was the opposite: guests experience more freedom in an ordered environment. A frequent visitor to Disneyland explained its appeal: "Because I can jaywalk and talk to strangers without fear." When the environment communicates coherent care, people relax enough to be spontaneous. Chaos produces defensive withdrawal; order produces openness.

Decision architecture as care

Hench cited the state fair in contrast: "everything clamors for you, so you look and look and try to make sense out of all these chaotic images. You are forced into making a lot of judgments." His design principle: at each decision point, offer only two choices. "We don't give seven or eight so that you really have to work hard to decide which is the best of those choices." You still get all seven or eight eventually, but they “unfolded gradually in segments to be less overwhelming."

Perfection as message

Hench learned the purpose of perfection from Walt Disney himself. At one point he had complained to Walt that the leather-strap suspension Walt wanted on new stagecoaches was excessive. "People aren't going to get this, it is too much perfection." Walt's response: "Yes, they will. They will feel good about it. And they will understand that it's all done for them."

Play precedes culture

Hench drew on Schiller's Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man to argue that play may precede human culture and "is vital to our survival as human beings."

Disneyland was a disruptive innovation. Hench’s understanding of human nature and the ability of people to absorb stimuli in a productive way is an enduring lesson for other purveyors of radically new things.

Circularity transformation is another radical new thing that could benefit from this lesson.

The Performance Economy's missing piece

One of the pillars of circular economy thinking is the concept of performance economy introduced by Swiss economist Walter Stahel. The core idea is that the value of products should be captured by their performance, not ownership.

This approach better aligns incentives and results in environmental and economic costs being incurred at the time of consumption. Hence, less wasteful production.

Stahel’s idea has become mainstream in the B2B context, where buy decisions are backed by analysis and well considered use cases. It underlies the groundswell towards operationalizing capital costs.

Among consumers, there are barriers to adopting this approach. Capital intensity is low for consumer products, which means the economic argument for access over ownership is less apparent. Consumer products are sold and bought on emotional grounds. Consumers take comfort from ownership.

One of the ways consumer preference towards ownership reveals itself is in subscription fatigue. This is particularly evident in entertainment, with renewed interest in physical media emerging over frustration with the streaming model.

Stahel solved the economics of ongoing relationships by selling use rather than objects, retaining ownership, and internalizing maintenance. But for consumers, the experience of these performance economy implementations produces fatigue, not reassurance.

Hench would have diagnosed that fatigue as a result of these services’ contradictions. The messaging says "we're here for you" while business logic says "we're optimizing your engagement." That contradiction, even subconscious, produces the low-grade vigilance Hench identified.

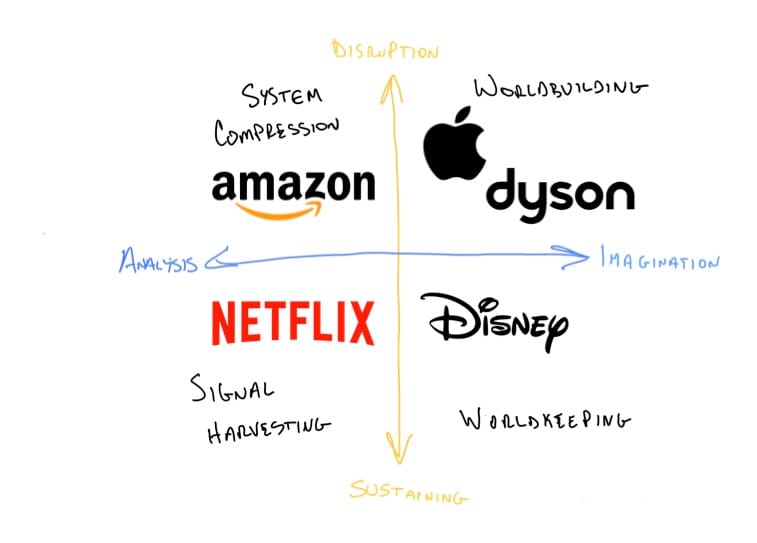

Recall the Innovation/Knowledge matrix from Empathy Is a Strategic Capacity. Netflix sits in Signal Harvesting—exquisitely tuned to revealed preference, extracting value from demand already in motion. No reassurance architecture. Its subscribers are more likely to feel surveilled than reassured.

The problem of subscription fatigue is evidence that solving economics without solving the architecture of the relationship is insufficient.

Reassurance is a strategic capability

In that essay, we argued empathy is the capability that unlocks the Worldbuilding quadrant, where disruption and imagination reinforce one another, and product–market fit must be imagined because markets and metrics don't yet exist. Empathy gets you into that quadrant.

But empathy alone is not sufficient for the long run. Reassurance is the capability that keeps you on the imagination side of the matrix over time. It's what makes imagined futures habitable.

This is how to understand Disney's position in Worldkeeping. No longer disruptive, it extends and preserves worlds it once built. But reassurance is so deeply embedded in its operations that it functions long after the founder's death, even after the disruptive impact has faded.

The parks go on eliminating contradiction. Every sightline still resolves. The stagecoach still has its proverbial leather-strap suspension. Reassurance has become institutional capability.

Apple and Dyson remain in Worldbuilding because they still have both: the empathetic imagination to envision futures on behalf of users and the reassurance architecture that makes those futures feel coherent and trustworthy once they arrive.

This approach was on display last week when Ferrari controversially revealed elements of its new EV in isolation, to be considered and judged on their own merits. The steering wheel, instrument binnacle, even individual switchgear panels were displayed on tables like objects in a gallery. The public is being given, in accordance with Hench’s doctrine, a series of small choices rather than one radical new reality to judge at once. Not a coincidence considering the designer of those elements is Jony Ive.

The meaning of perfection

Recall Hench’s story about Walt’s point about the stagecoach: "People aren't going to get this, it is too much perfection." Walt's response: "Yes, they will. They will feel good about it. And they will understand that it's all done for them."

This story reminds me of the lesson Steve Jobs learned from his father about finishing both sides of the fence:

“Even though it faces the wall and nobody will ever see it. You’ll know it’s there, so you’re going to use a beautiful piece of wood on the back. For you to sleep well at night, the aesthetic, the quality, has to be carried all the way through.”

Craft communicates relationship. Perfection isn't about making a favorable impression so much as signaling that someone cared enough to get it right, for you.

I have argued that joy is to circularity as quality was to lean: what looks like a knock-on benefit is actually the outward expression of the philosophy. Lean’s resolution of variance feels like quality.

Joy is what imagination plus reassurance feels like from the inside. It's the experiential evidence that contradiction has been eliminated; that the relationship is coherent all the way down to the leather-strap suspension. Or the back of the fence.

Joyless durability is the performance economy's version of the Gothic tower with the gasoline sign. Sound structure, contradictory experience. The opportunity cost of that joylessness scales with the duration of the relationship, even as Stahel's model demands longer relationships. The longer you ask someone to stay, the more the absence of reassurance compounds.

Circularity transformation needs Stahel's economics and Hench's architecture. Without both, you get either linear extraction dressed as service (subscription fatigue) or beautiful experiences without economic foundation. The integration is the point.

Subscribe to continue reading