"Something Goes Wrong!"

Why our stories won't contemplate the circular future we need — and how a quiet little film lights the way.

Last week's letter explored the role cultural mythology plays in telling meaningful stories that effectively shift public perspective. Today we dive deeper into why the selection of metaphor can mean success or failure. We begin where we left off: Joseph Campbell's observation "if you want to change the world, you have to change the metaphor".

- Something Goes Wrong!

- Why our stories can’t imagine the circular future we need — and how a quiet little film lights the way.

- I. The Vending Machine That Never Breaks

- II. Why Circularity Needs a Different Story Form

- III. Tomorrowland: The Right Ingredients, the Wrong Structure

- IV. Perfect Days Shows the Structure We Need

- V. How to Tell Stories This Way

- VI. Why This Matters Now

- VII. When Systems Hold

- Why This All Matters for the Circular Century

- Why our stories can’t imagine the circular future we need — and how a quiet little film lights the way.

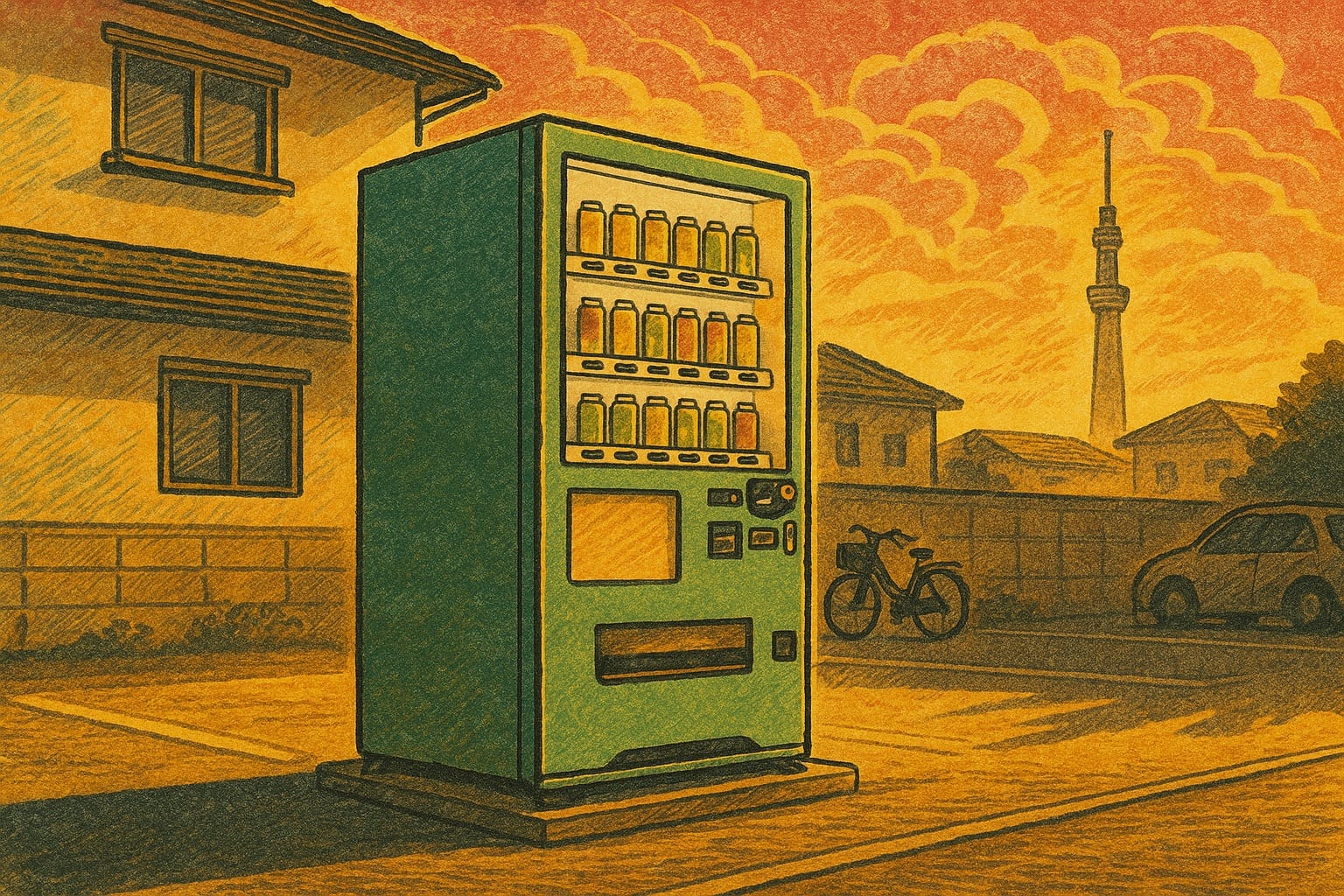

I. The Vending Machine That Never Breaks

Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days (2023) is a small story told with confidence. It follows Hirayama, a toilet cleaner in Tokyo, as he moves through his days with quiet precision: pruning trees, listening to cassette tapes, photographing shadows, and repeating the same steady rituals.

One part of that ritual stands out.

Every morning, he stops at the same vending machine for the same canned coffee.

It’s an unremarkable beat — so ordinary it feels invisible. Yet watching it, something feels strangely tense. The moment the coins go in, the audience waits for the modern story pivot: the rupture that kicks the “real plot” into motion.

Except here, it never arrives.

The machine works, every time. As you might expect in a functioning world.

Nothing goes wrong.

And because nothing goes wrong, the viewer begins to notice everything else: the softness of the morning light, the geometry of shadows, the care in Hirayama’s gestures. The reliability becomes the revelation.

This is a quietly radical move. In a culture whose dominant stories rely on rupture, Perfect Days reminds us of the emotional power of a world that works — a world that holds itself together long enough for us to feel its meaning.

And it points to a problem that transcends film, and explains the mythology gap that presents an opportunity for brands.

II. Why Circularity Needs a Different Story Form

Joseph Campbell said, “If you want to change the world, you have to change the metaphor.” One might interpret this as advice purely about messaging. But Campbell meant something deeper: the structure of a story sets the boundaries of what a culture can imagine.

Today, three narrative structures define the stories we consume. They show up everywhere — movies, theme parks, marketing, leadership keynotes, and strategy decks. The unifying theme: "something goes wrong."

Three Dominant Story Blueprints

| Blueprint | Core Pattern | What It Assumes |

|---|---|---|

| The Hero’s Journey | A stable world is broken → a hero responds → the world is repaired or remade | Meaning begins with rupture |

| Pixar’s Story Spine | Once upon a time… Every day… Until one day… Because of that… Until finally… | A rupture is required to launch the story |

| Imagineering’s “Something goes wrong!” Trope | Build the world → let guests enjoy it → then introduce a crisis | The exciting part starts when stability ends |

These structures work brilliantly for many storytelling goals. They are not the problem. The shared assumption underneath them—that stories “activate” only when something breaks — is the problem.

For circularity, this is a structural mismatch. A world built on continuity, stewardship, and regeneration cannot be imagined — much less desired — through metaphors optimized for rupture.

Roger Martin offers the operative insight: the future cannot be analyzed into existence.

Strategic thinking requires facility with a different kind of information than is normally used in business decisions. The object is to influence behavior of customers in the future. That means that there is no data because all data comes from the past. There is no data about the future. Thus, a strategic thinker needs to be comfortable with something other than statistically significant quantitative data…

One important form of qualitative information is analogy/metaphor, which Aristotle called the highest form of thinking: “The greatest thing by far is to have a command of metaphor…it is the mark of genius.” (Aristotle, Poetics)

Today, we need stories that not only entertain, but enlighten us about our destiny as emotional evidence. Tomorrowland once did this. EPCOT once did this. The 1939 World’s Fair did this at national scale.

III. Tomorrowland: The Right Ingredients, the Wrong Structure

Disney’s 2015 film Tomorrowland should have been a cultural touchstone, yet it disappointed critically and commercially. The ingredients were unusually strong:

Why Tomorrowland Looked Like a Guaranteed Success

| Creative Asset | Why It Mattered |

|---|---|

| Brad Bird (director) | One of Pixar’s finest structural thinkers; expert at the story spine |

| Damon Lindelof (writer) | A modern myth-maker skilled at building mystery and world logic |

| George Clooney | Global star power with cross-generational appeal |

| Michael Giacchino | A sweeping, emotionally rich score |

| Production Design | A vivid, aspirational future perfectly suited to world-inhabiting storytelling |

| Beloved IP (Tomorrowland) | A cultural shorthand for optimism and possibility |

Everything about the project signaled promise.

But Tomorrowland faltered — not because it was executed poorly, but because it obeyed the wrong metaphor. It used all three rupture-driven story structures described above.

The Core Issue

Tomorrowland promises utopia. But Tomorrowland’s structure requires crisis. It follows a classic rupture arc: a gifted hero is jolted out of her ordinary world (Hero’s Journey), the story turns on a sudden disruption that propels the plot (Pixar spine), and when the characters finally reach Tomorrowland, they discover that something has gone wrong! — a once-utopian world now in crisis, requiring them to fix the break.

The film does exactly what our dominant story forms reward — and in doing so, cancels its own premise.

Had the story form been closer to Perfect Days — dwelling, observational, experiential — the audience might have received what they came for: two hours in a future worth believing in.

IV. Perfect Days Shows the Structure We Need

Where Tomorrowland defers its world until crisis, Perfect Days lets us inhabit one from the first frame.

A rupture-first structure says: “You won’t feel meaning until the break.”

A dwelling structure says: “You will feel meaning because the world holds.”

The Emotional Logic of Perfect Days

| Narrative Element | What It Produces | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Repetition | Familiarity and rhythm | Makes the world feel lived-in |

| Continuity | Trust | Helps the viewer relax into the world |

| Competence | Respect for craft | Centers care and stewardship |

| Attention to detail | Beauty | Shows meaning in maintenance, nature |

| No rupture | Space for reflection | Allows coherence to become narrative |

The constancy of the vending machine is the symbol of this logic’s success. The viewer’s expectation of failure — and the story’s refusal to satisfy it — reveals how deeply rupture has shaped our sense of what stories “require.”

In that refusal, a new metaphor emerges: a world that works.

This is the kind of story the Circular Century needs.

V. How to Tell Stories This Way

Perfect Days isn’t the only film to succeed on this level of narrative + world creation. Others have built meaning from coherence rather than collapse.

2001: A Space Odyssey

Early in my career I got to meet Fred Ordway, one of the scientific advisors on 2001. He summarized Kubrick’s mandate this way: “Everything must work. No magic. No gaps in logic — only in practical knowledge.” This principle — designing a world that feels internally consistent and fully functional — is why 2001 still shapes our visual imagination of the future.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture

Unlike most Trek films, TMP combines a unique blend of ingredients: The full force of “the Roddenberry Box,” which forbade villains, malice, and easy dramatic shortcuts; a generous budget; and aerospace designers on the production team, who built the Enterprise as if it were a functioning institution in a spacefaring society. Together, these forces produced something rare in the franchise: a world that feels operational. The Enterprise presents as a working system — procedural, credible, and alive. TMP stands alone in the canon for its approach to drama without conflict in a functionally realized world.

WALL-E (Act I)

This is the exception that proves the rule about the Pixar spine. By stretching Act I far beyond typical length — and making it largely silent — Pixar allowed a world to form before the rupture arrived. WALL-E’s competence within that world is what generates empathy. His understanding of his environment, his mastery of routine, and his devotion to small acts of care place him in the same lineage as Dave Bowman in 2001 and Captain Kirk in TMP: protagonists defined by capability, not crisis. WALL-E resembles Hirayama this way too. The first act’s coherence makes the later rupture matter. It demonstrates that competence is its own form of emotional evidence.

VI. Why This Matters Now

We are living in a moment of consequence. We need planet-friendly systems that work — materially, culturally, economically. We need narratives that make such systems desirable.

That desire is what will shift demand to circularity.

But desire requires imagination. And imagination requires a story form that allows the future to be felt.

If every narrative requires collapse, audiences will never believe in the possibility of continuity. If the vending machine must break for the plot to “start,” then a world built on maintenance and care cannot feel dramatic, let alone aspirational.

The Circular Century needs stories where coherence is interesting, where rituals matter, where competence is emotionally satisfying, and where systems earn trust.

It needs the Perfect Days structure.

VII. When Systems Hold

The vending machine in Perfect Days is a metaphor for a future built on stability, attention, and care.

Each morning, it works. And because it works, meaning accumulates. A world that works becomes a world worth living in.

Trust is a function of coherence. A world that works does not lack narrative. It establishes belief.

If we want to change the world, we do have to change the metaphor. In Perfect Days, Wenders gives us one: a vending machine that never breaks.

If you are working on building the Circular Century: What’s your metaphor?

DYNAMO members get the full breakdown: how to adapt these story forms for your own projects and use worldbuilding as a strategic lever for the Circular Century. Join us below.

💬 Discuss this post: mention @christian@circudyne.com on Mastodon or your favorite fediverse app.

—

Subscribe to continue reading